|

The Lymphatic System | |

|

Functions of the lymphatic system:

1) to maintain the pressure and volume of the interstitial fluid and blood by returning excess water and dissolved substances from the interstitial fluid to the circulation. 2) lymph nodes and other lymphoid tissues are the site of clonal production

of immunocompetent lymphocytes and macrophages in the specific immune response.

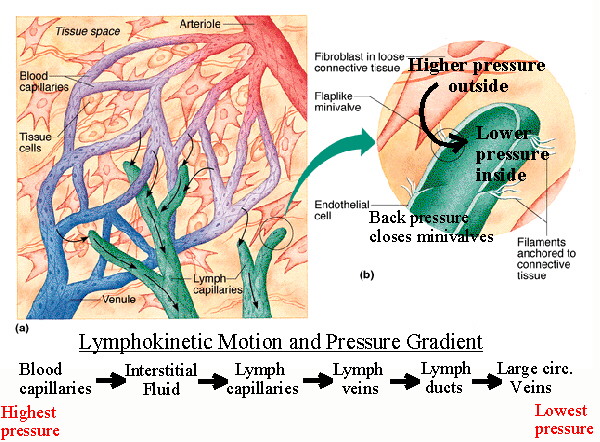

Filtration forces water and dissolved substances from the capillaries into the interstitial fluid. Not all of this water is returned to the blood by osmosis, and excess fluid is picked up by lymph capillaries to become lymph. From lymph capillaries fluid flows into lymph veins (lymphatic vessels) which virtually parallel the circulatory veins and are structurally very similar to them, including the presence of semilunar valves. |

|

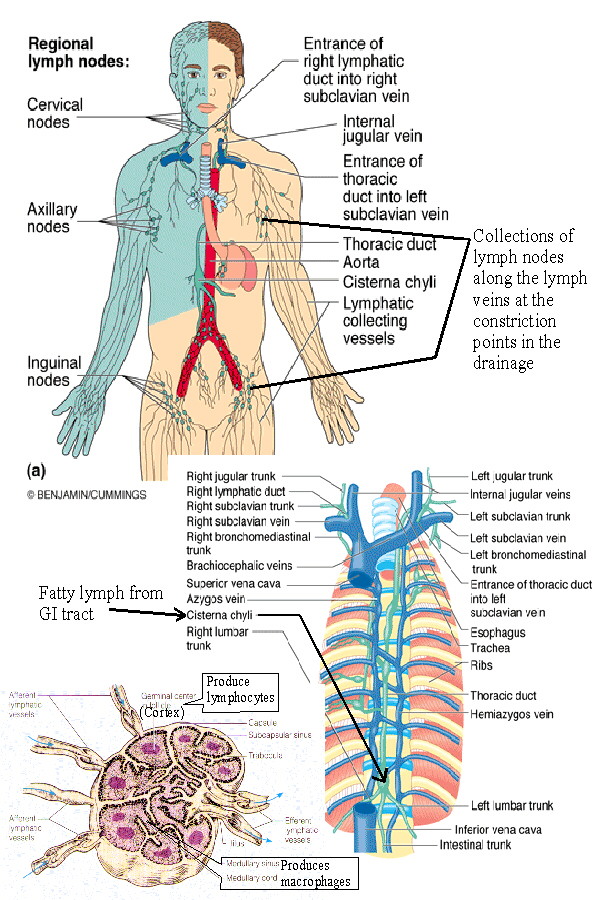

The lymphatic veins flow into one of two lymph ducts. The right lymph

duct drains the right arm, shoulder area, and the right side of the head

and neck. The left lymph duct, or thoracic duct, drains everything else,

including the legs, GI tract and other abdominal organs, thoracic

organs, and the left side of the head and neck and left arm and

shoulder.

These ducts then drain into the subclavian veins on each side where they join the internal jugular veins to form the brachiocephalic veins. Lymph nodes lie along the lymph veins successively filtering lymph. Afferent lymph veins enter each node, efferent veins lead to the next node becoming afferent veins upon reaching it. |

| Lymphokinetic motion (flow of the lymph) due to:

1) Lymph flows down the pressure gradient.

2) Muscular and respiratory pumps push lymph forward due to function of the semilunar valves. |

|

| Other lymphoid tissue:

1. Lymph nodes: Lymph nodes are small encapsulated organs located along the pathway of lymphatic vessels. They vary from about 1 mm to 1 to 2 cm in diameter and are widely distributed throughout the body, with large concentrations occurring in the areas of convergence of lymph vessels. They serve as filters through which lymph percolates on its way to the blood. Antigen-activated lymphocytes differentiate and proliferate by cloning in the lymph nodes. 2. Diffuse Lymphatic Tissue and Lymphatic nodules: The alimentary canal, respiratory passages, and genitourinary tract are guarded by accumulations of lymphatic tissue that are not enclosed by a capsule (i.e. they are diffuse) and are found in connective tissue beneath the epithelial mucosa. These cells intercept foreign antigens and then travel to lymph nodes to undergo differentiation and proliferation. Local concentrations of lymphocytes in these systems and other areas are called lymphatic nodules. In general these are single and random but are more concentrated in the GI tract in the ileum, appendix, cecum, and tonsils. These are collectively called the Gut Associated Lymphatic Tissue (GALT). MALT (Mucosa Associated Lymphatic Tissue) includes these plus the diffuse lymph tissue in the respiratory tract. 3. The thymus: The thymus is where immature lymphocytes differentiate into T-lymphocytes. The thymus is fully formed and functional at birth. Characteristic features of thymic structure persist until about puberty, when lymphocyte processing and proliferation are dramatically reduced and eventually eliminated and the thymic tissue is largely replaced by adipose tissue. The lymphocytes released by the thymus are carried to lymph nodes, spleen, and other lymphatic tissue where they form colonies. These colonies form the basis of T-lymphocyte proliferation in the specific immune response. T-lymphocytes survive for long periods and recirculate through lymphatic tissues. The transformation of primitive or immature lymphocytes into T-lymphocytes and their proliferation in the lymph nodes is promoted by a thymic hormone called thymosin. Ocassionally the thymus persists and may become cancerous after puberty and and the continued secretion of thymosin and the production of abnormal T-cells may contribute to some autoimmune disorders. Conversely, lack of thymosin may also allow inadequate immunologic surveillance and thymosin has been used experimentally to stimulate T-lymphocyte proliferation to fight lymphoma and other cancers. 4. The spleen: The spleen filters the blood and reacts immunologically to blood-borne antigens. This is both a morphologic (physical) and physiologic process. In addition to large numbers of lymphocytes the spleen contains specialized vascular spaces, a meshwork of reticular cells and fibers, and a rich supply of macrophages which monitor the blood. Connective tissue forms a capsule and trabeculae which contain myofibroblasts, which are contractile. The human spleen holds relatively little blood compared to other mammals, but it has the capacity for contraction to release this blood into the circulation during anoxic stress. White pulp in the spleen contains lymphocytes and is equivalent to other lymph tissue, while red pulp contains large numbers of red blood cells that it filters and degrades. The spleen functions in both immune and hematopoietic systems. Immune functions include: proliferation of lymphocytes, production of antibodies, removal of antigens from the blood. Hematopoietic functions include: formation of blood cells during fetal life, removal and destruction of aged, damaged and abnormal red cells and platelets, retrieval of iron from hemoglobin degradation, storage of red blood cells. See also [Hodgkin's Disease][Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma] |

|

NEXT: Immune System