By DAVID CORREIA

Aaron Swartz committed suicide nearly a month ago, almost two years to the day after he was arrested by federal authorities for “illegally” downloading millions of scholarly articles from the academic database JSTOR. Despite JSTOR’s request that no charges be brought against Swartz, US Attorney Carmen Ortiz of Massachusetts charged Swartz with two counts of wire fraud and eleven violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. If convicted he would have faced up to 35 years in prison. He was 26 years old when he hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment.

Aaron Swartz in 2009 at a Wikipedia meeting in Boston. Photo by Sage Ross. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Obituaries remembered him as having lived a remarkable life for someone so young. He was the founder of Infogami, an ambitious effort that was part of the Open Library project. He was an original contributor (at 15-years old) to Creative Commons, a flexible copyright format designed as an alternative to private property. More recently, he was an influential force behind efforts to scuttle the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), a bill that Swartz and others recognized as written by media conglomerates in order to shut down open-source, peer-to-peer file sharing websites—sites that industry sees as a threat to commercial control of creative content online.

As these efforts make clear, Swartz’s political activism did not take the form of retaliatory distributed denial-of-service hacktivist revenge attacks characteristic of Anonymous, nor were they vague statements in support of internet freedom. Rather, Swartz was a vocal and influential critic of the narrow, commercial notion of intellectual copyright that threatened the form and function of digital social interaction online.

His download of five million JSTOR articles is a case in point.

According to prosecutors, Swartz, at the time a fellow at Harvard University’s Ethics Center Lab on Institutional Corruption, entered an unlocked network closet in an MIT basement in December of 2010. There he connected an old laptop with a huge external hard-drive to cables that linked the computer to MIT’s network. Before leaving he hid the computer under a cardboard box. Over the course of the next few weeks, the computer slowly downloaded millions of articles from the online academic storage service JSTOR, a digital file sharing service founded by a consortium of universities for the more efficient distribution of academic content. Today, more than 7,000 institutions in more than 150 countries subscribe to JSTOR in order to access scholarly articles.

Lawrence Lessig, a mentor to Swartz and a prominent Harvard Law professor, lashed out at the aggressive prosecution. “From the beginning,” he wrote, “the government worked as hard as it could to characterize what Aaron did in the most extreme and absurd way. The ‘property’ Aaron had ‘stolen,’ we were told, was worth ‘millions of dollars’ — with the hint, and then the suggestion, that his aim must have been to profit from his crime. But anyone who says that there is money to be made in a stash of ACADEMIC ARTICLES is either an idiot or a liar.”

While Lessig is correct that Swartz had no intent, nor means, to profit from downloading articles from JSTOR, he couldn’t have been more wrong when he suggested that there was no money to be made by controlling access to academic scholarship.

Swartz targeted JSTOR precisely because of the way JSTOR reinforces dubious intellectual property claims by commercial publishers of academic journals who claim the exclusive rights to what should be open-access material. JSTOR, in other words, controls and limits the distribution of scholarship conducted by public employees, or produced by scholars with public funds, to only those with paid subscription access. It limits much of that access by terms-of-service agreements that amount to the privatization of an intellectual commons. And the money it collects from subscriptions is distributed to the commercial publishers of public knowledge—not the authors, researchers, or institutions that produce it.

It’s a strange state of affairs. Scholars usually work for public universities, or conduct research under publicly funded grants and fellowships or, if they work at private institutions, teach students who attend their private colleges via publicly supported grants and loans. These scholars conduct research and write articles and do all the work to produce scholarly journals. And instead of that work being freely available, it becomes the exclusive property of a handful of huge transnational corporations.

This is a recent and troubling pattern. In less than one generation universities worldwide divested themselves almost completely of their obligation to support academic publishing and distribution. Today, few universities publish and distribute scholarly material in journal form but still demand that their faculty publish such material. Scholars therefore have little choice but to publish with commercial outlets.

Knowing that, these publishers do little to support this work. Scholars don’t just publish their work in commercial outlets, they do all the work to bring it to print. They do the vetting, the editing, and the production. The commercial publishers pay for none of this work. They just cash the checks when universities buy it back from them.

Elsevier, for example, claims the exclusive copyright on more than a quarter million articles written each year by scholars in the 2,000 journals it owns. It sells access to those journals via ScienceDirect, a database that serves as its electronic platform. In 2010, Elsevier reported a profit margin of 36 percent on revenues of $3.2 billion. Its profits from the sale of access to scholarly journal articles accounts for 28 percent of the revenues of the Reed Elsevier group (₤1.5 of 5.4 billion in 2006).

Interested in accessing the work of scholars who publish path-breaking work in the prestigious journal Biochimica et Biophysica Acta? If so, your library will have to pay Elsevier a $20,930 annual subscription fee. Between Elsevier, Springer, and Wiley, 42 percent of all academic articles are owned privately.

So much for Lessig’s suggestion that there’s no money in academic publishing. And this was exactly Swartz’s complaint. The public funds the production of scholarly work, scholars produce this intellectual work, and then a few private companies cash in on it. But it wouldn’t take much to break the back of commercial control of this intellectual and creative commons. The expertise, infrastructure, and resources to do so already exist. But instead of serving as a powerful platform for the collective production and open-access distribution of scholarly work, JSTOR blindly accepts the ridiculous copyright claims of firms like Elsevier and therefore reinforces, rather than disrupts, the continued commodification of scholarly production. According to The Atlantic, JSTOR “turns away 150 million attempts to read journal articles” due to lack of subscription.

Swartz sought to do what thousands of academics do already on a daily basis: freely distribute scholarly material in patterns that violate exclusive commercial copyright as both a form of protest and a commitment to the open-access and wide distribution of scholarly material.

While JSTOR did not want to pursue charges against Swartz, MIT’s role has been more troubling. An internal review is underway, and many anticipate it could reveal that MIT played a critical role in the investigation that led to charges against Swartz. MIT has long been an institution committed to intellectual freedom and open-access—at least its faculty have been. The administration is another story.

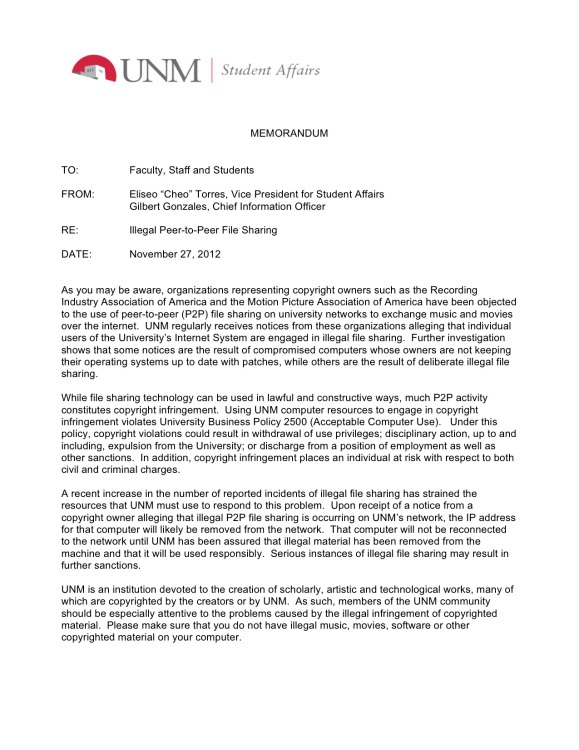

This eroding commitment to intellectual freedom is not solely a problem at MIT. Recent events at the University of New Mexico suggest that a reactionary politics of copyright has also seized certain University of New Mexico administrators. On November 27, 2012, and again last month just days after the furor erupted following Swartz’s death, UNM’s Vice President for Student Affairs, Eliseo Torres, and its Chief Information Officer, Gilbert Gonzalez, distributed a threatening memorandum to all faculty, staff, and students at the university.

The memo reads as follows:

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Swartz never advocated the copyright infringement of material produced for commercial exchange, what he did was question the logic of exclusive copyright claims to particular kinds of intellectual and creative works that circulate online.

It’s a distinction the University of New Mexico also makes, but in a much different way. Like thousands of other institutions, UNM relies on a commercial file-sharing platform called eReserves as a way for its faculty to easily distribute scholarly material to students in digital formats. The University apparently believes that the use of eReserves does not constitute copyright infringement because the files are password-protected and circulate among University students who, presumably, have legal access to these files by virtue of their status as students.

This is true only in theory. In practice, faculty sometimes wish to share a book for which the library has no copy, or need to post sections of a book that the bookstore was late in ordering. While the librarians involved with eReserves are very cautious of copyright infringement issues, eReserves exists in a kind of copyright grey area. There are times and situations in which the University arguably (according to existing copyright law) infringes the copyright laws that it seeks to defend. But it only does so when honoring copyright contradicts the mission of the University. Copyright, in other words, constitutes a set of negotiated social (and increasingly technical) arrangements regarding the ways and patterns that intellectual material circulates. Copyright does not exist apart from the conditions that create it. And the promise and possibilities of digital formats to intellectual production has meant that the patterns of circulation often violate the letter of copyright law while honoring the spirit.

The University often errs on the side of whatever advances its educational mission. This attention to context in the application of copyright law evaporates, it appears, when powerful corporate interests weigh-in; the University then capitulates to corporate claims to copyright and threatens its students for violating the letter of the law.

But for many activists the strict private property copyright claims of industry trade groups like the Recording Industry Association of America and the Motion Picture Association of America are as equally dubious as those of Elsevier. For open-access advocates, the aggressive enforcement efforts by media trade groups to claim exclusive copyright, which are enthusiastically taken up by law enforcement agencies and then blindly accepted by even non-commercial networks such as the University of New Mexico, amount to a vast digital enclosure.

Consider the fact that the businesses represented by the RIAA and MPAA owe their very ability to distribute digital content over the internet (and increasingly their ability to produce it in the first place) to the collective, non-commercial work of computer programmers like Aaron Swartz who, over two generations, have built a vast peer-to-peer, file sharing network as a way to connect people and ideas in new and exciting ways—ways that had everything to do with often utopian social ideals and almost nothing to do with making a buck.

The University of New Mexico got it ridiculously wrong when it said, “much P2P activity constitutes copyright infringement.” No, a more compelling argument can be made that the internet, both practically and legally, cannot serve as a means to circulate material under an exclusive copyright claim.

First, it is impossible in practical terms. The intellectual property claims of the entertainment industry appear laughable given the ease with which copyrighted material circulates online in ways that exceed its control. As much money can be made violating copyright as defending it. Hence, the proliferation of advertising-based P2P file sharing programs, low-cost secure cloud storage sites, and for-fee ISP anonymizers. Can’t make money selling content? Make money distributing someone else’s.

More importantly, however, the business model defended by the RIAA and MPAA amounts to a form of digital squatting. They had nothing whatsoever to do with the design and construction of the digital infrastructure through which their products circulate. They’re the bully who commandeers the playhouse after the neighborhood kids spend all summer building it. And now that bully wants to charge the kids a fee for each social interaction they have within that clubhouse (or they borrow the Facebook model and capture, aggregate, and eventually monetize the “friendship” that goes on in the clubhouse).

It sounds absurd when put this way, but (and this is the really astounding part) nearly everyone thinks this is all just fine.

Except for people like Aaron Swartz, who imagine a different world.

This article first appeared in La Jicarita